When I started looking into this subject, I predicted a person’s physical attractiveness would only have minor advantages. I was wrong.

In fact, I was so wrong, that in one study, the effects of physical attractiveness on judges were so influential, they fined unattractive criminals 304.88% higher than attractive criminals.

Surprising, I know.

Before we proceed, I want to address a few concerns of mine. Firstly, the information that you will read may cause some readers to feel unsettled. This is not my intention. Yes, it is disheartening. But the purpose of this article is to inform lawyers and other decision makers so that they can use the attractiveness bias to their advantage or to counter it.

A second concern of mine is that I don’t want to over-emphasise the attractiveness bias. Judges and jurors are affected by all kinds of cognitive distortions, such as emotive evidence, time of day, remorse of the defendant, socioeconomic status, race, gender, anchoring effect, and the contrast bias.

In the first section of this article, I give a ‘straight-to-the-point’ summary of the research conducted by 27 studies. Next, I enter into greater depth on the attractiveness bias and its effects on judges, jurors, and lawyers. Lastly, I provide research on the attractiveness bias in everyday life. Arguably, the last section is the most interesting.

Enjoy!

* * *

Key Takeaways

Physical Attractiveness had a significant influence on judges sentencing. The more unattractive the criminal, the higher the sentence. Or conversely, the more attractive the criminal, the lower the sentence. The results of three studies show a minimum increase of 119.25% and a maximum increase of 304.88%.

Attractiveness had little to no effect on a judge’s verdict of guilt. Attractive and unattractive criminals were convicted equally.

Mock jurors generally sentenced unattractive criminals significantly higher than attractive criminals. However, as jurors do not determine sentencing in real court cases, these results are not directly applicable.

Attractiveness had minor effects on mock juror’s verdicts. Some studies reported minor effects and some studies reported no effects.

Generally, attractive people are perceived as more intelligent, more socially skilled, more appealing personalities, more moral, more altruistic, more likely to succeed, more hirable as managers, and more competent. Attractive people tend to have better physical health, better mental health, better dating experiences, earn more money, obtain higher career positions, chosen for jobs more often, promoted more often, receive better job evaluations, and chosen as business partners more often, than unattractive people.

I believe that the attractiveness bias is rarely conscious. I do not think people are consciously disfavouring unattractive people. I also do not place moral blame on the typical person for their unconscious bias.

* * *

‘Attractiveness Bias’ in the Legal System

REAL JUDGES: SENTENCING

THE MISDEMEANOUR STUDY [1]

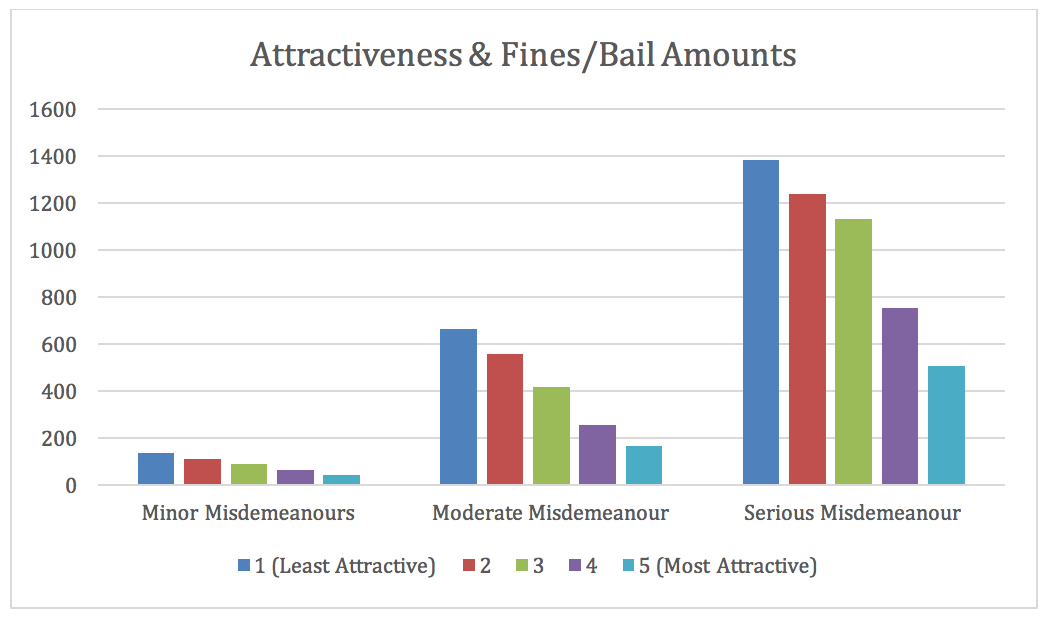

The first study we will observe is the research conducted by Downs and Lyons.

The purpose of this study was to find a link between a criminal’s attractiveness and sentencing outcomes.

They gathered a group of police officers and students to rate the attractiveness of over 2000 criminals. A scale of 1 - 5 was used and their ratings were mostly similar.

Then, the judges sentencing decisions were divided into two main categories: misdemeanors and felonies. Misdemeanors were separated into to 3 classes, related to the severity of the crime.

The Results & Key Takeaways

For misdemeanours, the judges fined unattractive criminals significantly more than attractive criminals. The fine incrementally increased as the attractiveness decreased.

1. Minor Misdemeanours = +224.87%

2. Moderate Misdemeanours = +304.88%

3. Serious Misdemeanours = + 174.78%

The results are graphed below.

Curiously, felony fines had no correlation with the attractiveness of the criminal. The study does not make it clear why this is the case.

Answers to Possible Objections

The judges varied in gender and race.

There was no correlation between sentencing outcomes and age, gender, and race.

Weaknesses

For privacy reasons, the specific crime was not documented.

The direction of causation is not known. I enter into more depth in the section entitled ‘causation’.

THE PENNSYLVANIAN STUDY [2]

In Pennsylvanian and Philadelphian courts, the researcher’s gathered data on 67 defendants. The defendants were a mix of black, Hispanic, and white and there were 15 real judges in total.

Results & Key Takeaways

On average (mean), criminals of low attractiveness were sentenced to 4.10 years in prison and criminals of high attractiveness were sentenced to 1.87 years in prison. This equals a 119.25% increase.

Weaknesses

All observers were white.

THE SECOND PENNSYLVANIAN STUDY [3]

This study was similar to the previous study. The researchers recorded data from real court cases in Pennsylvania. They detailed the physical attractiveness of 60 defendants and their neatness, cleanliness, and quality of clothing. Then, they recorded the judge’s decisions.

The criminals were charged with a range of felonies, including ‘murder; manslaughter; rape; kidnapping; armed robbery; aggravated assault; indecent assault; arson; burglary; conspiracy to sell/delver heroin, cocaine, hashish, and other elicit drugs; extortion; fraud; theft; and firearms violation.’

They were also a mix of white, Hispanic and black.

Results & Key Takeaways

The unattractive defendants were punished higher than the attractive defendants.

Weaknesses

The study did not give specific results. This is a major disappointment.

CONCLUSIONS

Unattractive criminals were punished higher than attractive criminals in three studies. The lowest increase was at 119.25% and the highest increase was at 304.88%.

REAL JUDGES: VERDICT, GUILTY OR NOT-GUILTY

There was no association between the defendant’s physical attractiveness and the judge’s verdict. Attractive and unattractive criminals were found guilty at equal rates. Zebrowitz and McDonald [4] also found that the plaintiff’s attractiveness had little to no effects on a judge’s verdict.

THE BABY-FACED STUDY [5]

The following study is not directly related to physical attractiveness but it is related to physical appearance.

Zebrowitz and McDonald measured the effects of defendants with a ‘baby-face’ and the judge’s verdict decisions. This is a strange characteristic to measure, however, the results were significant enough to warrant attention.

‘Baby-faced adults tend to have larger eyes, thinner, higher eyebrows, a large forehead and a small chin, and a curved rather than an angular face.’[6] A team of participants sat in 421 cases in ‘6 branches of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts small claims courts. 3 judges heard 51% of the cases and the remaining 49% of the cases were presided over by 22 additional judges.’ ‘62% of the plaintiffs and 78% of the defendants were male. 96% of both plaintiffs and defendants were white, and 81% were between the ages of 21 and 50.’

Results & Key Takeaways

The more baby-faced an adult was, the less likely he/she was found to be guilty for ‘intentional actions’ in civil claims. Observe the graph below.

Interestingly, baby-faced adults had no effects in claims of negligent actions.

MOCK JURY: SENTENCING

Before I present the following research, I need to address a major limitation. Jurors do not decide upon sentencing, thus, the following results may not have direct application.

THE META-ANALYSIS STUDY [7]

A meta-analysis examined 25 studies on the effects of physical attractiveness on mock jurors. They found that mock jurors gave higher sentences to unattractive criminals than attractive criminals. This was only for crimes of rape, robbery, and negligent homicide. For swindle, the punishment was equal. The physical attractiveness of the victim also had no effects on the jurors.

THE BURGLARY STUDY [8]

In this study, the participants were given a burglary scenario along with an image of the criminal. Some received the unattractive criminal and others received the attractive criminal. 10 psychology students rated the attractiveness of the criminals prior to the study to determine attractiveness.

Then, they were asked to suggest a 1, 5, 10, 15, or 20 years imprisonment.

‘[The] participants consisted of 40 Euro-American men, 40 Euro-American women, 40 African- American men, and 40 African-American women.’ A strength of this study is the participants ranged in race, gender, and age.

Results & Key Takeaways

The attractive criminal was given an average sentence of 9.7 years, and the unattractive criminal was given 14.7 years. That’s an increase of 51.55%.

Weaknesses

The researchers measured more items than simply attractiveness. This means that the 160 participants were not all measured on attractiveness. As they measured 8 different items and only two of them on attractiveness, I infer that the sample size consisted of 40 participants.

Jurors may be influenced by the mannerisms of criminals and victims. In this study, photographs were used, thus the jurors could not be influenced in that way.

MORE STUDIES

The attractiveness bias may affect civil cases also. Kulka and Kessler presented the participants with an audio-video showing an automobile negligence case. The mock jury consistently awarded fewer damages to the unattractive defendant.[9]

In Desantts and Kayson’s mock trial, the mock jurors were given a burglary scenario. The only changing factor was the attractiveness of the defendant. The unattractive defendant was given a higher sentence than the attractive defendant.[10] In another mock burglary trial, the jurors gave higher sentences to the unattractive defendant. However, in the swindle trial, higher sentences were given to the attractive defendant. It was hypothesised that the attractive defendant used her attractiveness in the swindle case, and the jurors held this with disapproval.[11] Smith and Hed found the same results. The unattractive burglar was sentenced higher but the attractive swindler was sentenced higher.[12]

CONCLUSIONS

It’s clear that mock jurors possess a bias against unattractive defendants.

For negligent homicide, robbery, burglary, and civil negligence, unattractive defendants were sentenced higher than attractive defendants.

For swindle cases, attractiveness bias seems to have the reverse effect.

However, jurors do not make sentencing decisions, thus, these results do not have direct application.

MOCK JURY: VERDICT, GUILTY OR NOT GUILTY

There is a clear distinction between what jurors believe to be ethical and what jurors actually decide. One study surveyed a series of mock jurors and found that 93% thought physical appearance should not be considered when evaluating guilt.[13] It’s reasonable to assume that jurors are not consciously associating physical attractiveness with guilt and sentencing.

THE META-ANALYSIS STUDY [14]

A meta-analysis examined 25 studies on the effects of physical attractiveness on mock jurors. They found Mock jurors find unattractive defendants guilty more often than attractive defendants. However, the results were not significant.

THE CANADIAN SEXUAL ASSAULT STUDY [15]

125 university students participated in this study. All students were white and Canadian.

The focus was to test the effects of white jury members perceptions of the physical attractiveness of white victims of rape. Were defendants found guilty more often when the plaintiff was attractive?

Participants read a four-page trial excerpt that included opening and closing statements from the Crown and Defence lawyers, and testimony from both the defendant and the victim. In the excerpt, it is specified that the victim and the defendant are colleagues, and the victim invited the defendant over to her home for dinner. Both the victim and the defendant agree that sexual intercourse occurred, but the victim alleged that the sexual intercourse was forced, whereas the defendant maintained that it was consensual.

Key Takeaways

Victim Attractiveness:

34.8% of men thought the defendant was guilty with an attractive victim and 52.3% of women thought the defendant was guilty with an attractive victim. Most men were not confident in their decision. Women were neutral in their confidence. This means, women were more likely to find a defendant guilty when the victim was attractive.

65.2% of men thought the defendant was guilty with an unattractive victim and 47.4% of women thought the defendant was guilty with unattractive victim. Most men were confident in their decision. Women were neutral in their confidence. This means men were slightly more likely to find the defendant guilty with an unattractive female victim.

Men seem to be influenced more by a female victim’s attractiveness than women. Women seem to be more consistent regardless of a female victim’s attractiveness.

Weaknesses

The mock jurors were university students and the average age was 20. The victim was always female and white.

MORE STUDIES

The attractiveness bias may affect civil cases also. Kulka and Kessler presented the participants with an audio-video showing an automobile negligence case. The mock jury consistently gave more guilty verdicts to unattractive defendants.[16]

CONCLUSIONS

Unattractive defendants are found guilty slightly more often than attractive defendants. However, these results are not significant. Many studies found no difference between attractive and unattractive defendants.

Men are more influenced by a female victim’s attractiveness in cases of sexual offenses. They are slightly more likely to decide in favour of the unattractive victim.

MOCK JURY: GENERAL PERCEPTIONS

Esses and Webster’s found that mock jurors perceived the unattractive defendant as significantly more dangerous.[17]

In Efran’s mock trial, he found that the jurors were more certain of the unattractive defendant’s guilt. When the attractive defendant was guilty, the jurors were less certain of their decision.[18]

Researchers found that when the victim was innocent and attractive, less evidence was needed to find the defendant guilty. Conversely, when the victim was unattractive, more evidence was needed to find the defendant guilty. However, when the victim was perceived to have contributed to the crime due to carelessness, attractiveness had no effect.[19]

In a rape mock jury trial, the attractive victim was more likely to be believed to be a victim of rape than the unattractive victim. The unattractive victim was less believed and even thought to have provoked the rapist.[20]

DEFEATING THE ATTRACTIVENESS BIAS

There are several factors that can offset the effects of the attractiveness bias.

THE SLOW THINKING STUDY [21]

The purpose of the study was to find out whether the attractiveness bias could be reduced by rational thinking.

124 female students were given a summary of a murder case. Half of the women were given a clear case of murder and the other were give a case of uncertainty, that is, it was hard to determine whether the defendant was guilty. The other factor that changed was the attractiveness of the defendant. One was unattractive and the other was attractive.

Results and Key Takeaways

The scenario where the criminal is clearly guilty, the women gave higher sentences to the unattractive criminal (24.71 years), than the attractive criminal (15.11 years). This amounts to a 63.53% increase. [See image below]

In the case where the criminal’s guilt is unclear, attractiveness had minimal effect on the sentencing amount. [See image below]

This study suggests that thinking slowly may help reduce the attractiveness bias. It seems that rapid thinking makes one susceptible to such psychological distortions. Even when the defendant is clearly guilty, slow thinking would be beneficial to reduce excessive sentencing.

Weakness

Only female students were tested.

THE REAL CONSEQUENCES STUDY [22]

Some researchers are skeptical that real jurors will have the same biases as the studies in simulated juries. The term ‘simulated jury’ is misleading. Studies do not ‘simulate’ a jury in the way we visualise the word. Instead, researchers generally gather students, give them a booklet of information, then get them to answer some questions at the end. Simulated juries miss many of the characteristics found in real court cases.

This study attempted to prove their skepticism. The researchers attached a real consequence to the answers the students provided. One group was told that their verdict would result in the loss or saving of a staff members job. The other group was given the same scenario but were told that no consequences would result of their verdict.

Results and Key Takeaways

83% of the ‘real consequences’ group voted the teacher guilty. 47% of the ‘no consequences’ group voted the teacher guilty. They repeated the studies a few times with variations and received similar results.

The ‘real consequences’ group retained more of the case information than the ‘no consequences’ group. However, the interest between groups was equal.

MORE STUDIES

Mock jurors that deliberate are less likely to be influenced by the attractiveness bias. Thus, mock jurors that make their decision independently, are more likely to be influenced by the attractiveness bias.[23] However, another study found that deliberation exaggerated the effects of the attractive defendant.[24]

In one study, guilty defendants that smiled received lesser sentences than guilty defendants that did not smile.[25] Another study showed that defendants who displayed high levels of repentance and remorse received significantly lower sentences by mock jurors.[26]

A LAWYER’S PHYSICAL ATTRACTIVENESS

IN COURT

I was unable to find any studies directly addressing the physical attractiveness of a court advocate.

However, the late David Ross, a QC from Melbourne Australia, believes the physical attractiveness of the advocate is neither a positive or a negative. He writes:

Good physique is not a necessity. Advocates are tall, short, fat, thin, good looking, plain. No doubt the good looking advocate has some attraction, but being well-favoured is probably the least of the qualities an advocate needs. An unhappy physique or unusual looks are never a handicap to one who has the necessary attributes.[27]

It must be noted that his belief was grounded in experience, not empirical research.

IN A LAW FIRM

I have found no journal articles on physical attractiveness and men in a law firm. Thus, the focus of this section will be on women.

Peggy Li examined the current scientific literature on the effects of physical attractiveness upon people’s perceptions.[28] Then, she made inferences on how this would affect women in the legal profession.

It is important to note that the author’s conclusions are predictions. Her article is not an empirical study itself. Nonetheless, the academic journal article was well researched.

Key Takeaways

Women that are searching for a job in the legal industry may have greater success if they’re physically attractive.

Women in the legal profession that are attractive may have more success than their unattractive peers as they are perceived in a more positive light. This is caused by a blend of many factors.

If a woman dresses ‘sexily’, she may be negatively perceived. Both men and women may perceive her as using her body to ‘get ahead.’

Weaknesses of the Article

The journal article itself is not an empirical study. Thus, Peggy Li is making an informed prediction.

All scientific literature that the author referenced are observations on white women. Women of other races may have different conclusions.

CAUSATION

I have been writing thus far as if physical attractiveness is causing the above results, rather than physical attractiveness just being correlated. This is in part misleading as scientific causation has not fully been established, or ever will be.

There are many explanations of the link between attractiveness and litigation outcomes. Here are a few:

The relationship of attractiveness to litigation processes may be of four basic types.

First, it may be that persons who are less attractive commit more serious crimes than those who are more attractive. This view suggests that unattractive people are more inclined toward crime, especially violent crime.

The second view is that criminal actions elicit differential perceptions of objective attractiveness, so that attractiveness estimates are modified by prior knowledge of the actions of the persons being judged.

Third, attractiveness and antisocial/criminal behaviors are tightly pleached, probably from an early age. Because their associations are routinely high, it is probable that the direction of effects between attractiveness and such behavior will remain unknown.

Finally, it may be possible that a third variable affects the relationship of attractiveness and criminal accusations/activities. Socioeconomic status, ethnicity, and developmental advantages (e.g., nutrition, schooling) might be such factors.[29]

And:

...the finding of a significant negative correlation between seriousness of crime and attractiveness could possibly suggest that unattractive persons are more likely to be suspected of criminal activity, and consequently charged with a serious crime, than are their more attractive counterparts. Contrariwise, one could argue that unattractive persons are more likely to engage in criminal activities because their lesser endowment in looks obviates legitimate means of value-access.[30]

However, the incremental changes of the correlation between attractiveness and sentencing[31] weighs heavily on the probability of a causal link (refer to ‘The Misdemeanour Study’ above).

The association between socioeconomic status and physical attractiveness is probably ruled-out for the following reasons. Firstly, one study found that the defendant’s clothing was not correlated to their physical attractiveness.[32] However, I hypothesise there would be exceptions in extreme circumstances such as homelessness. Secondly, many studies found no correlation between race and physical attraction, thus ruling out the race, socioeconomic status, and physical attraction association.

While causation is not known, I place my bet that physical attraction will have noteworthy effects on judicial outcomes.

* * *

The General Effects of the Attractiveness Bias

GENERAL PERCEPTIONS OF ATTRACTIVE PEOPLE

We seem to perceive attractive people more favourably than unattractive people on many measures.

We perceive attractive people as: more intelligent[33]; more socially skilled[34]; possessing more socially desirable qualities[35]; more appealing personalities[36]; more likely to generally succeed[37]; more altruistic[38]; and more moral[39]. Also, ‘people are more likely to give help to strangers who are dressed neatly and attractively.’[40]

The converse is also true, that is, unattractive people are perceived as less intelligent, less socially skilled and so on. Interestingly, the effects are heightened by the ‘contrast bias’. When an attractive person is directly compared to an unattractive person, the attractive person is seen as more attractive and the unattractive person is seen as less attractive.[41]

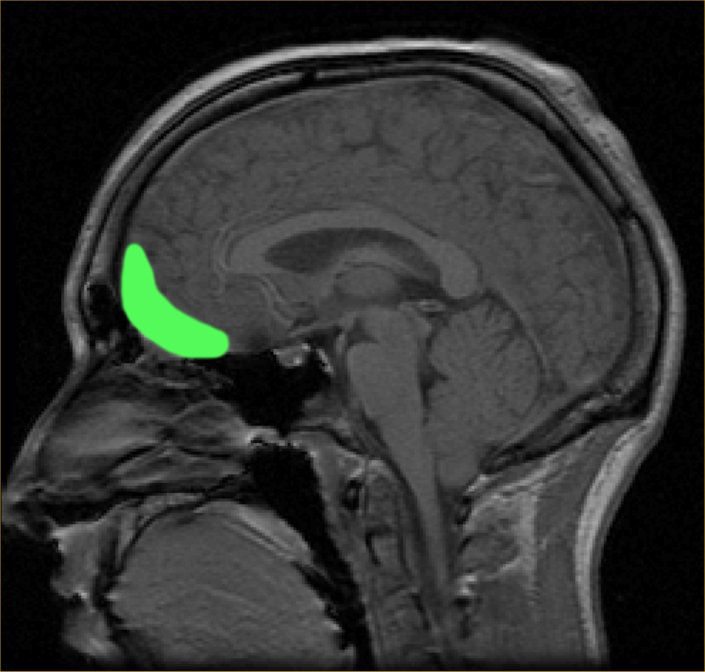

When a person comes into to contact with an attractive person, it triggers certain parts of the brain.

Activity in the medial orbitofrontal cortex ("OFC"), the region of the brain associated with processing positive emotions, stimuli, and reward, increases as a function of both attractiveness and moral goodness ratings.[42]

Similarly, activity in the insular cortex, a region of the brain associated with processing negative emotions and pain, increases as a result of unattractiveness and negative goodness ratings.[43]

[Image is taken from Systematic Meta-Analysis of Insula Volume in Schizophrenia (2012) by Alana M. Shepherd, Sandra L. Matheson, Kristin R. Laurens, Vaughan J. Carr & Melissa J. Green]

ATTRACTIVENESS AND LIFE OUTCOMES

Not only are attractive people perceived more positively, they outperform unattractive people on several measures.

Attractive people outperform unattractive people on ‘occupational success, popularity, dating experience, sexual experience, and physical health’.[44] Studies have even found that attractive people have better mental health, both from subjective experience and on objective psychological measures. Lastly, attractive people tend to have higher career positions and earn more money.[45]

ATTRACTIVENESS AND CAREER SUCCESS

There are strong correlations between physical attractiveness and career success for both men and women. The attractiveness bias in the workforce is well and truly present.

Attractive people are perceived as: more hirable as managers[46] and more competent, however, this effect is stronger for males than for females.[47] Attractive people are hired more often, promoted more often, found more suitable, chosen as a business partner more often, and have better performance evaluations than unattractive people.[48]

Attractive people are chosen for employment more often even when the unattractive people have equal qualifications.[49] Studies have attempted to lessen this effect by presenting more information about the applicants, such as ‘relevant past work experience, relevant college major, interview transcripts, performance reviews’[50] etc. It’s hoped that this will offset the attraction effects. However, this is not supported. More information about the applicants did not ‘even the playing-field’.[51] It must be noted that this is only relevant when choosing between similar prospects. For example, a company would not hire a person with zero qualifications for a position that requires a Ph.D.

Professionals were affected by the attractiveness bias as much as university students.[52] The experience of the hiring manager did not lessen the effects.

There is a silver-lining here. The effects of the attractiveness bias are decreasing over time. The effects of attractiveness were stronger in studies conducted in the 1970’s and weaker in the studies conducted in the 1990’s. It must be noted, that the effects were clearly there in the 1990’s. Thus, while it’s reducing, it still exists.

Women and Physical Attractiveness

In a meta-analysis, the researchers evaluated all the major studies from 30 years of research related to physical attractiveness and job success. The evidence is clear, the ‘beauty is beastly’ effect is not supported.

The ‘beauty is beastly’ effect tries to argue that attractive women in stereotypically masculine jobs will be discriminated against because their attractive qualities emphasise their feminine qualities. These feminine qualities are seen not to ‘match’ the stereotypical masculine job. Thus, they believe that the masculine woman or the unattractive woman will be favoured. This is false.

Attractive women will be privileged, even in stereotypically masculine jobs. The author quotes, ‘thus, our results afford no support for the “beauty-is-beastly” perspective: Physical attractiveness is always an asset for individuals.’[53]

* * *

Visual Summary

The following infographic is a visual summary of this article.

References

[1] Natural Observations of the Links Between Attractiveness and Initial Legal Judgments (1991) by A. Chris Downs and Phillip M. Lyons

[2] Defendant's Attractiveness as a Factor in the Outcome of Criminal Trials: An Observational Study (1980) by John E. Stewart

[3] Appearance and Punishment: The Attraction-Leniency Effect in the Courtroom (1985) By John E. Stewart

[4] The Impact of Litigants' Baby-Facedness and Attractiveness on Adjudications in Small Claims Courts (1991) by Leslie A. Zebrowitz and Susan M. McDonald

[5] The Impact of Litigants' Baby-Facedness and Attractiveness on Adjudications in Small Claims Courts (1991) by Leslie A. Zebrowitz and Susan M. McDonald

[6] The Impact of Litigants' Baby-Facedness and Attractiveness on Adjudications in Small Claims Courts (1991) by Leslie A. Zebrowitz and Susan M. McDonald

[7] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness, Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Gender of Defendants and Victims on Judgments of Mock Jurors: A Meta-Analysis (1990) by Ronald Mazzella & Alan Feingold

[8] Defendants' Characteristics of Attractiveness, Race, And Sex and Sentencing Decisions (1997) by Andrea DeSantis & Wesley A. Kayson

[9] Is Justice Really Blind? - The Influence of Litigant Physical Attractiveness on Juridical Judgment (1978) by Richard A. Kulka and Joan B. Kessler

[10] Defendants' Characteristics of Attractiveness, Race, and Sex and Sentencing Decisions (1997) by Andrea Desantts, Wesley A. Kayson

[11] Beautiful but Dangerous: Effects of Offender Attractiveness and Nature of the Crime on Juridic Judgment (1975) by Harold Sigall & Nancy Ostrove

[12] Effects of Offenders' Age and Attractiveness on Sentencing by Mock Juries (1979) by Edward D. Smith & Anita Hed

[13] The Effect of Physical Appearance on the Judgment of Guilt, Interpersonal Attraction, and Severity of Recommended Punishment in a Simulated Jury Task (1974) by Michael G. Efran

[14] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness, Race, Socioeconomic Status, and Gender of Defendants and Victims on Judgments of Mock Jurors: A Meta-Analysis (1990) by Ronald Mazzella & Alan Feingold

[15] The Influence of Defendant Race and Victim Physical Attractiveness on Juror Decision-Making in A Sexual Assault Trial (2014) by Evelyn M. Maeder, Susan Yamamoto, & Paula Saliba

[16] Is Justice Really Blind? - The Influence of Litigant Physical Attractiveness on Juridical Judgment (1978) by Richard A. Kulka and Joan B. Kessler

[17] Physical Attractiveness, Dangerousness, and the Canadian Criminal Code (2006) by Victoria M. Esses & Christopher D. Webster

[18] The Effect of Physical Appearance on the Judgment of Guilt, Interpersonal Attraction, and Severity of Recommended Punishment in a Simulated Jury Task (1974) by Michael G. Efran

[19] Beautiful and Blameless: Effects of Victim Attractiveness and Responsibility on Mock Juror’s Verdicts (1978) by Norbert L. Kerr

[20] Rape and Physical Attractiveness: Assigning Responsibility to Victims (1977) Clive Seligman, Julie Brickman, & David Koulack.

[21] What is Beautiful is Innocent: The Effect of Defendant Physical Attractiveness and Strength of Evidence on Juror Decision-Making (2015) by Robert D. Lytle

[22] Guilty or Not Guilty? A Look at the "Simulated" Jury Paradigm (1977) by David W. Wilson and Edward Donnerstein

[23] Attractive But Guilty: Deliberation and the Physical Attractiveness Bias (2008) by Mark W. Patry

[24] The Emergence of Extralegal Bias During Jury Deliberation (1990) by ROBERT J. MacCOUN

[25] Attributions of Guilt and Punishment as Functions of Physical Attractiveness and Smiling (2005) M.H. Abel & H. Watters

[26] Communication and justice: Defendant Attributes and Their Effects on the Severity of His Sentence (1974) by Steven K. Jacobson & Charles R. Berger

[27] Advocacy by David Ross QC

[28] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[29] Natural Observations of the Links Between Attractiveness and Initial Legal Judgments (1991) by A. Chris Downs & Phillip M. Lyons

[30] Defendant's Attractiveness as a Factor in the Outcome of Criminal Trials: An Observational Study (1980) by John E. Stewart

[31] Natural Observations of the Links Between Attractiveness and Initial Legal Judgments (1991) by A. Chris Downs & Phillip M. Lyons

[32] The Impact of Litigants' Baby-Facedness and Attractiveness on Adjudications in Small Claims Courts (1991) by Leslie A. Zebrowitz and Susan M. McDonald

[33] The Attractive Executive: Effects of Sex of Business Associates on Attributions of Competence and Social Skills (1985) by Midge Wilson, Jennifer Crocker, Clifford E Brown, & Janet Konat

[34] The Attractive Executive: Effects of Sex of Business Associates on Attributions of Competence and Social Skills (1985) by Midge Wilson, Jennifer Crocker, Clifford E Brown, & Janet Konat

[35] The Attractive Executive: Effects of Sex of Business Associates on Attributions of Competence and Social Skills (1985) by Midge Wilson, Jennifer Crocker, Clifford E Brown, & Janet Konat

[36] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[37] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[38] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[39] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[40] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[41] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[42] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[43] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[44] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[45] The Impact of Physical Attractiveness on Achievement and Psychological Well-Being (1987) by Debra Umberson & Michael Hughes

[46] Physical Attractiveness and Femininity: Helpful or Hurtful for Female Attorneys (2015) by Peggy Li

[47] The Attractive Executive: Effects of Sex of Business Associates on Attributions of Competence and Social Skills (1985) by Midge Wilson, Jennifer Crocker, Clifford E Brown, & Janet Konat

[48] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[49] Sexism and Beautism in Personnel Consultant Decision Making (1977) by Thomas Cash, Barry Gillen, & D. Steven Burns

[50] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[51] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[52] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

[53] The Effects of Physical Attractiveness on Job-Related Outcomes: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental Studies (2003) by Megumi Hosoda, Eugene F. Stone-Romero, Gwen Coats

![[Image is taken from Systematic Meta-Analysis of Insula Volume in Schizophrenia (2012) by Alana M. Shepherd, Sandra L. Matheson, Kristin R. Laurens, Vaughan J. Carr & Melissa J. Green]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5817bb2746c3c4a605334446/1489460712103-9M0KKA4399C6CP4423E8/image-asset.png)